I recently crossed the 6-month post-surgery milestone. It wasn’t too long ago that I was in a sling, unable to independently put on a shirt due to my immobility. During that time, I was significantly limited in the many daily activities I took for granted, from dressing myself to showering. In those first few weeks, I often thought: is this the reality of aging? What if this were permanent?

The thought is perhaps a bit dramatic, but I would argue it’s not too farfetched to imagine losing our physical abilities at some point in life. To prepare for this potential scenario, I thought it would be a helpful exercise (no pun intended) to consider what it might be like to have physical limitations and what we can do about it, today.

What Are the Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)?

Activities of Daily Living are defined as the day-to-day, self-care tasks we need to perform to live (and likely take for granted). Healthcare professionals often evaluate individuals’ independence and quality of life based on their ability to perform them.

Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADLs) include:

- Ambulating or transferring (aka moving; e.g., getting in and out of bed/a chair, walking, etc.)

- Bathing and personal hygiene (e.g., bathing/showering, brushing teeth/hair, etc.)

- Toileting (e.g., the ability to use the toilet appropriately, sitting and standing up, and cleaning oneself)

- Note: some consider continence, or the ability to control our bladder and bowels, also a BADL

- Dressing (e.g., putting clothes on and taking them off, including using zippers and buttons)

- Feeding (aka the act of eating; e.g., using cutlery, etc.)

There are a broader, more complex set of ADLs called IADLs (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) that suggest one’s capacity to live independently, but for the purpose of this article we’ll focus strictly on the basic ADLs.

Notice that none of the BADLs are neurocognitive. In other words, these are the purely physical abilities we need to live. One could argue neurocognitive abilities are equally, if not more important, to healthy aging than physical abilities. But that is a topic for another day.

ADL Limitations Progressively Increase with Age

We may think the loss of these abilities is a far-off proposition. But the reality is we will likely lose one or more of these at some point in our lifetime, should we be lucky enough to live long enough.

The most acute and common cause for younger individuals to lose their ADLs is injury and illness, albeit usually only for a short time. However, as we age and the recovery process becomes more difficult, there is a chance (perhaps a likelihood) that we don’t regain the full physical capacity we had before the injury or illness.

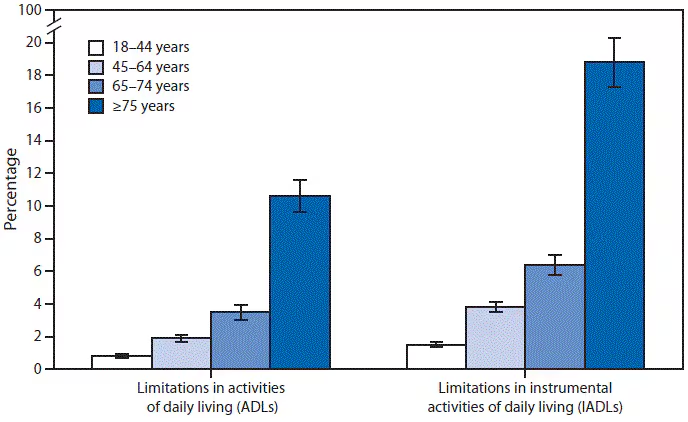

As the below chart depicts, people gradually lose their ability to perform ADLs and IADLs with age, with the most accelerated deterioration occurring around the age of 75 and beyond. If we plan (or hope) to maintain a certain independence and quality of life past this threshold, we have to actively preserve these basic abilities for as long as possible.

How to Fight ADL Decline

There are several methods in which we can think about training to preserve our physical abilities and/or prepare ourselves for a potential decline:

Simulate the loss of any given function/ability

For anyone who has sustained an injury, this method will be pretty familiar. For example, I lost the ability to use my right arm for about 2 weeks post-shoulder surgery. During this time, I had to contort, compromise, and flat-out avoid certain activities due to this limitation. As a result, I gained valuable perspective as to the value of maintaining a healthy, well-functioning shoulder for activities like dressing and bathing.

Therefore, we can artificially simulate how difficult life would be should we lose any of our current physical abilities by taking one away for a day, week, month, etc. Try performing all tasks in a given day without using a particular limb or forcing yourself to avoid activities of a certain variety, such as anything involving climbing stairs; I can assure you it will be eye-opening!

Make daily activities harder

Perhaps a more positive and uplifting approach to this endeavor is to focus on improving our current physical abilities. Importantly, this approach doesn’t necessarily need to include hours of weightlifting in the gym. Instead, we can gradually strengthen our muscles by increasing physical stress in manageable amounts using any, or a combination, of the following variables: weight, speed, heat, time.

- Weight – it probably comes as no surprise that muscles strengthen when forced to adapt to increasing weight demands. As an example of making daily activities harder through weight, consider the difficulty of wearing a weighted vest or backpack all day. Walking, sitting, standing…everything becomes a little more difficult due to the added weight. Over time, just by doing the same daily activities with weight will strengthen all of the muscles we use without thinking much about it.

- Speed – our bodies have to work harder to perform physical tasks faster. Running vs. walking is a common example, but by simply focusing on performing daily chores like vacuuming, mowing the grass, etc., at a faster pace can serve as a means to level up our conditioning.

- Heat – for anyone who has sat in a sauna, or been outside in a summer heat wave, it’s difficult to do much of anything physically. As such, caution is warranted when leveraging this variable. However, so long as we stay hydrated, performing activities where the temperatures are higher will also have beneficial physical effects. Even in winter where ambient temperatures are colder, wearing several layers of clothes can create an artificially hot environment.

- Time – muscular endurance comes with exposure to prolonged periods of physical demand. For example, weeding the garden for an hour will feel a lot harder than ten minutes, despite the relatively low-intensity nature of the activity. Similarly, shampooing our hair for a minute or two vs. 20 seconds will surely cause a nice burning sensation in the shoulders from the effort.

Your Future Self Will Thank Your Current Self

Funny enough, I came up with the idea for this post in the depths of my post-surgical malaise. It is often in sub-optimal circumstances that we wish we weren’t there in the first place and seek to avoid being there in the future.

To the extent possible, look for ways to make your daily activities more difficult. It might look and feel silly now when we can perform these effortlessly, but our future selves will hopefully thank our present selves for being overprepared for older age.

Reader Questions

- What are your favorite ways to “level up” daily activities?

- What experiences have you had that made you appreciate your ability to perform basic daily tasks?