I recently completed the first diet of Module 2 in the All of Us Nutrition for Precision Health (NPH) study. For two weeks I had all my meals and snacks prepared for me, just like a meal delivery service. Here’s what I learned.

Meal Delivery Sure Is Convenient

I’ve always been a meal prepper. Bulk cooking on Sunday saves a lot of time and energy during the busy work week and helps me better control what and how much I eat over the course of the week. Admittedly, I am also a bit obsessed with having control over the ingredients that go into my food, both in quality and quantity.

As a result, I’ve never really entertained meal delivery services like Hello Fresh, Trifecta, or Purple Carrot, to name a few. Generally speaking, relative to a home-cooked meal, I found these products to be more expensive on a per meal basis, insufficient on a calorie/quantity basis (i.e., not enough food), and suboptimal from a nutritional standpoint, or a combination of all three.

However, with the NPH study, I had the opportunity to live as if I were on a meal delivery service. For two weeks, the program provided breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks according to my calorie needs given my activity level. Not only that, they were paying me to do so! All I had to do was pick up the prepped food every 3-4 days and document what I was eating (ok, so it wasn’t exactly “delivery”, but close enough).

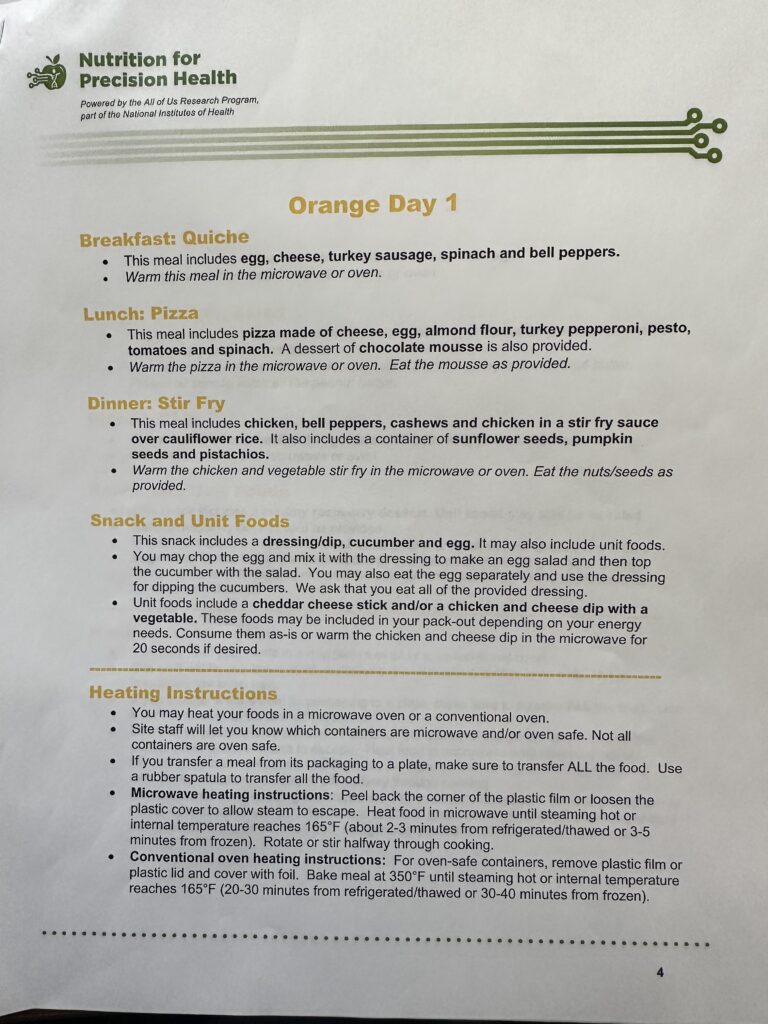

Example of a day’s menu

The first few days were exciting, as the meals were new and different (not what I would typically eat). I also had two weekends where my mind was free of grocery lists, recipes, and meal prepping, which was a big time saver.

As the diet continued, I started to get bored. The menu cycled every three days, so by the time the two-week period was up, I had eaten the same breakfast/lunch/dinner/snacks combo 4-5 times.

What didn’t wear off, though, was the convenience of simply pulling a container of food out of the fridge when I needed it, no prep required. This amounted to a huge mental weight being lifted, such that I rarely felt food anxiety around where my next meal was coming from. In this way, I can see the value of meal delivery services, even if they are a little more expensive than home cooking.

Dieting is Inherently Calorie Restrictive

The NPH study is designed to be isocaloric; in other words, it is meant to provide participants with a similar amount of calories to what they normally eat. As such, it is not meant to result in weight loss or weight gain. However, I lost weight. Why did this happen?

A typical day’s worth of food

I would argue that dieting of any kind is more likely to result in calorie restriction. Whether it is saying “I am not going to eat X or only eat Y”, “I am only going to eat within the hours of X and Y”, or “I am only going to eat X amount of food,” we are exerting influence over how many calories we are consuming. In all likelihood, this heightened consciousness results in our eating fewer calories.

It is challenging enough to calibrate our own caloric needs; it is even harder for an independent third party like a research study dietician or a meal delivery service to portion out how much we need to eat. For me, despite voicing my activity level and caloric needs on numerous occasions, the study still underestimated how much food I would need to maintain a similar weight and hence I lost weight. However, by focusing on weight, I realize I lost sight of other metrics that may be far more important to my long-term health.

Two Weeks is Not Enough Time for Noticeable Changes

Throughout the two-week period, I had numerous measurements and biological samples taken: heart rate, blood pressure, body composition, glucose monitoring, and a marathon final session of blood draws.

One of the first observations I had of the diet was that it was seemingly far saltier than I typically eat. As a result, I expected at least some change in markers like blood pressure that have been associated with diets high in sodium. But at each visit, I noticed only small, insignificant changes in this metric.

Another measure I was particularly interested in was body composition, especially given my weight loss. As it turns out, the results showed that all of my weight loss was fat; my lean body mass was identical at day 1 and day 14, while my body fat percentage dropped. Consequently, it would appear my focus on resistance training during these past two weeks likely helped preserve muscle, even when in a caloric deficit.

That said, while I was able to draw some conclusions and reinforce some actions based on the data provided during this study, it is clear that two weeks’ worth of blood pressure and body composition measurements are unlikely to correlate with long-term health outcomes. With that in mind, it will be important for me to continue tracking these measures to influence how they change over time.

Reflections

Overall, I enjoyed my first two-week diet experiment in NPH. Being on a meal “delivery” service was certainly a convenience I’d consider paying for in the future, if the meals being provided met the right nutritional criteria. I have additional diet periods to complete over the spring/summer, and I hope it will be similarly enlightening to monitor my body’s response to the different diets offered.

As always, I will be attuned to the physical and biological measurements that are taken throughout the study. What I’ve learned is that these point-in-time measures of blood pressure, body composition, etc. are only valuable if we continue to monitor and use them to inform our long-term health actions.

About Nutrition for Precision Health (NPH)

NPH is a nutrition research study seeking to understand how individuals respond to different diets. Module 2 is comprised of three, two-week diet periods where participants are provided pre-prepared food calibrated to their caloric needs. Before, during, and after the diet period, vital signs and biological samples are taken and analyzed to understand how that individual responded to the diet. Learn more here.